Before the railway

The Parkland Walk is in the hilly part of North London. The hills are known as the Northern Heights. The old main road from London to York and Edinburgh had a notoriously steep section on Highgate Hill as it rose to the toll gate at the top of the ridge (the High Gate). Thomas Telford eased the problem in the 1820s by building the Archway Road as he improved the route from London to Holyhead and bypassed Highgate Village and its hills. Those same hills were a challenge to the railway builders who had to consider how to get visitors from London to Alexandra Palace. They managed it by following Hornsey Ridge from Finsbury Park to Highgate looping round to Muswell Hill. Hornsey Ridge is where a layer of blue clay breaks out. It is the strata under London in which the tube railways were built. Muswell Hill is a left over from the Ice Age and is the terminal moraine of the ice sheet that once covered much of the country.

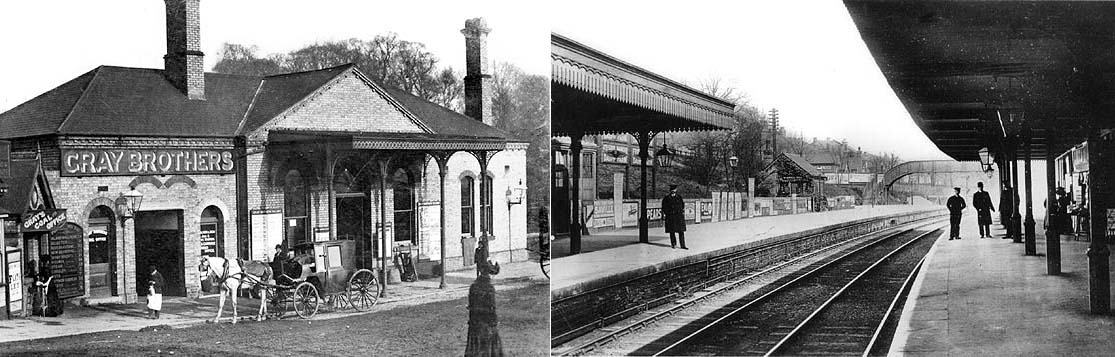

Life as a railway

The railway line, part of which now forms the route of the Parkland Walk, started as a steam service off the East Coast Main Line with suburban services for the Great Northern Railway. The line was authorised in 1862 for construction to Edgware as the Edgware, Highgate and London Railway and it was opened in 1867, by which time the EH&L had been absorbed by the Great Northern.

This survey map (1862 -1869) shows the route of the Edgware Highgate and London Line leading out from Finsbury Park in the bottom right corner, westwards along Hornsey Ridge through tunnels to Highgate Station.

The map predates the Muswell Hill Alexandra Palace extension which would soon follow around the western boundary of ‘Gravel Pit Wood’, later known as ‘Highgate Wood’.

The site chosen for Alexandra Palace was a hill formed by the terminal moraine of a glacier in the last ice age – Muswell Hill. It wasn’t possible to build the track directly to the Palace from Finsbury Park as the gradients were too steep for steam trains so an extension was built from Highgate around what is now Highgate Wood. There were additional stations at Cranley Gardens and Muswell Hill

The Palace and the new railway line opened on 2nd June 1873. 100,000 people attended the opening but sixteen days later the Palace caught fire and by the end of July passenger services ceased.

By 1907 trams and bus services were providing more direct routes to the Muswell Hill and competition for provision of transport services grew.

The Palace reopened in 1922 but its popularity was on the wain. Rail services were poor and those who did visit Alexandra Park tended to use the much better bus and tube services.

In the late 1930s there was an ambitious plan to expand the Underground that then terminated at the station we now know as Archway (it was Highgate at the time and was renamed in 1940 to avoid confusion with the LNER Highgate – the present station). A long tunnel was built under the Archway Road and the old steam lines north of Highgate became part of the Underground system.

Much of the engineering work, started as the war broke out, was never fully commissioned. The present Cape building at Crouch Hill was built as a transformer station. The designation of the ‘Green Belt’ after the war killed the economic case for the alterations and the advent of better buses combined with suspensions due to a coal shortage in 1952 saw the end of passenger services on the southern parts in 1954. The tracks from the Highgate depot to Finsbury Park were retained for shuttling stock to the Drayton Park to Moorgate section of the Northern Line.

The last passenger train ran on July 3rd 1954. Over the following ten years, freight services continued to decline until the last train ran on 29th September 1970 and the tracks were finally lifted in 1971.

Most of the land was acquired in stages by Haringey and Islington councils. A section of the land around the perimeter of Highgate Woods between Highgate and Muswell hill remains the property of London Underground to this day.

If you would like more in depth information on the railway history we recommend you get hold of a copy of Jim Blake’s ‘Northern Wastes’ or visit the website ‘Disused Stations’, or trainstobeyond.com.

Repurposing the old railway

The short 750-metre section in Muswell was the first to be adopted as the beginning of the Walk. It’s worth looking out for the few indications that this was at one time being prepared to be part of the Northern Line Underground extension. You can still see ironwork for carrying electricity cables and concrete ducts either side to direct the cables under the track. The cables are now buried but still used to deliver electricity to the Northern line.

The second longer section of the Parkland Walk from Archway Road to Finsbury Park experienced a more turbulent process prior to being adopted. Initially housing schemes had been proposed and this was met with strong opposition by the community which had become fond of the green space. A public inquiry found against the housing proposals and recommended maintaining ‘the natural character of the area’ as a valuable amenity.

A further challenge to the future of the site was a proposal in the mid 1980s by the Department of Transport for the construction of a six-lane motorway. This met with fierce opposition from both the council and local people and a campaign to ’Save the Parkland Walk’ was spearheaded by the newly formed Friends of the Parkland Walk. By 1989 the road scheme was abandoned as it was recognised that it would have ‘unacceptable environmental consequences’.

Local Nature Reserve

In 1980 David Hope, Haringey’s newly appointed warden faced the challenge of transforming a derelict site, blighted by dereliction, flooding and fly tipping, into a site of nature conservation with an accessible path for the public. It’s worth stating that the hoggin path, which was funded by TfL, ran out of budget and the eastern end was not laid to the full spec. This is one of the reasons why it is currently in a very poor condition.

During the stewardship of the railways, the grassy embankments and cuttings had been maintained by regular cutting and burning. When this ceased, tall herbs, brambles, and other shrubs were able to colonise and the nature of the vegetation slowly changed. This was a welcome development as this enabled the establishment of different habitats for a wider range of plants and animals.

In 1990, Haringey Council declared the Walk a Local Nature Reserve under the provisions of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949 and the Parkland Walk was give some welcome protections so that the community could enjoy tranquility and nature in the heart of the urban hullabaloo. Sadly, within a year, Haringey’s Conservation Unit, responsible for most of the Nature Reserve’s management, was disbanded as part of council cutbacks and management quickly declined.

The Parkland Walk has become a popular local asset and its popularity has extended far afield. Visitors from overseas are guided to visit the Parkland Walk as part of their London experience. Such popularity, and the increased awareness locally which grew dramatically during the periods of Covid19 lockdown, have resulted in the Walk become increasingly crowded, especially at weekends.

Aspirations to address the ecological decline in the form of a management plan in 2008 went unadopted by Haringey Council, in part due to the removal of funding from central government. As a result, ecological succession has continued unchecked across large parts of the land and after a period of ecological fine health and wide diversity, the Parkland Walk has now become increasingly dominated by dense woodland which has choked ground flora and led to the disappearance of many species of plant, and the associated invertebrates, along with some significant wildlife.